Burma’s Western Border as Reported by the Diplomatic Correspondence

(1947 – 1975) Aye Chan

(Kanda University of International Studies, Japan)

(a) Introduction

If one explores the diplomatic records of the British Commonwealth in the National Archives in London, two files bound with the corresponding letters between the British Embassy in Rangoon, the Foreign Office in London, the High Commissioner of the United Kingdom in Karachi, Pakistan and the Deputy High Commissioner of the United Kingdom in Dacca (Dhaka) will be found in the accession to the Southeast Asia Collection. According to the British Archival Law, they were kept secret as government documents until 1979 and 2005. Both files consist of the correspondence between these diplomatic missions, regarding Burma-East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) border problems. Burma (Myanmar) was a British colony until 1948 and the Arakan (Rakhine State) that shares an international boundary of 45 miles was the first Burmese province annexed to British India after the First Anglo-Burmese War (1924-26). The Naaf River serves as the border between the two countries. These documents have shed lights on new information on the Jihadist movement of the Chittagonian residents (so-called Rohingya) in North Arakan, the illegal cross-border migrations and the communal violence on Burma’s western frontier in the first decade of independent Burma.

(b) On the Mujahid Rebellion in Arakan.

The Mujahids of Chittagonian Muslims from North Arakan declared jihad on Burma after the central government refused to grant a separate Muslim state in the two townships, Buthidaung and Maungdaw that lie along the East Pakistani (present-day Bangladeshi) border. The Mujahid movement launched before Burma gained independence and hassled the resettlement program for the refugees in the Buthidaung and Maungdaw Townships. During the war, the Arakanese inhabitants of Buthidaung and Maungdaw were forced to leave their homes.

The people of Buthidaung fled to Kyauktaw and Minbya where the Arakanese were the majority. The Arakanese from Maungdaw were evacuated to Dinajpur in East Bengal by the British officials. Even though the British administration was reestablished after the war, the Arakanese were unable to return to their homes.

“For want of funds only 277 out of about 2400 indigenous Arakanese, who were displaced from Buthidaung and Maungdaw Townships after the British evacuation in 1942, could be resettled on the sites of their original homes. There are also two thousand Arakanese Buddhist refuges brought for fear of Muslims’ threatening and frightening them by firing machine guns near the villages at night. While our hands are full with internally displaced refugees we cannot take the responsibility for repatriation of the Muslim refugees from the Sabirnagar camp which the government of India is pressing.[1]”

The Muslim refugees from the camp at Subirnagar were also unable to resettle in the interior part of Akyab District at Alegyun, Apaukwa and Gobedaung. All 3,000 of them were first sent to Akyab Island. Two Muslim Relief Committees were formed in Akyab and Buthidaung in order to give assistance possible to refugees. The proposal to send about 1,500 refugees in small batches to the Muslim villages in Buthidaung Township for the time being was accepted. The District Welfare Officer was instructed to work out the expense for transport and supporting building materials.[2]

In August 1947, the Sub-Divisional Officer of Maungdaw, U Tun Oo, was brutally murdered by the Muslims. The Commissioner of Arakan reports:

“I have no doubt that this is a result of a long fostered communal feeling by the Muslims. The assassins who committed the murder were suspected to be employed by the Muslim Police Officers and have been organizing strong Muslim feelings and dominating the whole areas. This is a direct affront and open challenge to the lawful authority of the Burma Government by the Muslim Community of Buthidaung and Maungdaw Townships whose economic invasion of this country was fostered during the British regime. Unless this most dastardly flouting of the government is firmly and severely dealt with, this alien community will try to annex this territory or instigate Pakistan to annex it.[3]”

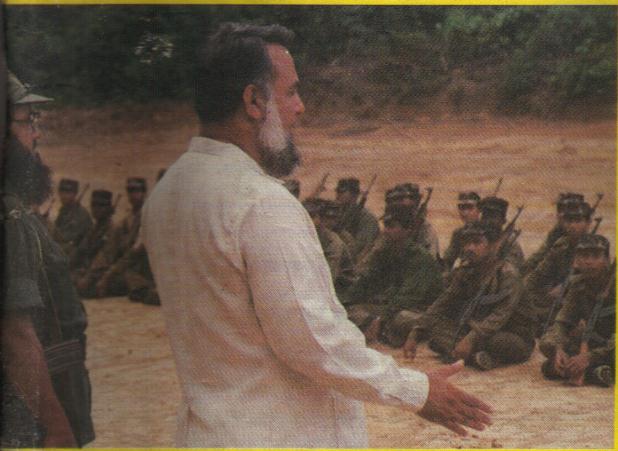

The newly independent republic had to cope with the insurgency of Karen ethnic group and the communists in the country after gaining independence in 1948. Major cities were captured by the Communists and Karen rebels. Two battalions of its regular army went underground to join the communists. The Capital City, Rangoon, was surrounded by the Karen rebels. The Union government was scrawled in the international newspapers with the epithet of “Rangoon Government.” In such a situation only a few hundreds troops from the Battalion (5) were sent to the western front to fight the Mujahids. About the objective and strength of the Mujahids, the British Embassy in Rangoon reports to the Foreign Office in London on February 12, 1949.

“It is hard to say whether the ultimate object of the Muslims is that their separate state should remain within the Union or not, but it seems likely that even an autonomous state within the Union would necessarily be drawn towards Pakistan. The Mujahids seem also to have taken arms in about October last, although this does not exclude the possibility that some have not gone underground and are still trying to obtain their objective by agitation only. There are perhaps 500 Muslims under arms, although the total number of supporters of the movement is greater.[4]”

Buthidaung and Maungdaw were under the control of the government forces but the countryside around the town was out of control.

One report gives a detailed account of the visit of Prime Minister U Nu and the Supreme Commander of the Burmese Army, Lieutenant General Smith Dun to Akyab in October of 1948. It says that the local officials in East Pakistan provided information and aid to the insurgents from across the border. The Sub-Divisional Officer and the Township Officer from Cox’s Bazaar were reported to have supplied the Muslim guerrillas with arms and ammunition. The wounded rebels were apparently able to obtain treatment from the hospital in Cox’s Bazaar. According to the report of the Deputy Commissioner of Chittagong Hill Tracts, both the commissioner and the Burmese officials were informed that the two Mujahid leaders, Jaffar Meah and Omra Meah, were hiding in Balukhali village in East Pakistan, near to the Burmese border.[5] The British Embassy in Rangoon sent a confidential letter to the High Commissioner for the United Kingdom in Pakistan on February 28, 1949; this letter dealt with the probability of provocation and interference from local Pakistani officials on the other side of the border. It reads:

“In spite of the correct attitude of the Pakistan Central Government there have been fairly reliable reports that their local officials in, for instance, Cox’s Bazaar have actively helped Muslim guerrillas. You yourselves are well aware of the pro-guerrilla attitude in this affair of the Pakistan district officers. The Pakistan Government must also be aware of it, and we feel that if they do not curb these officials they may run the risks of provoking Anti-Muslim riots in Akyab district as bad as those which occurred during the war.[6]”

The main financial source of the Mujahid Party was the smuggling of rice from Arakan to East Pakistan. Their actions were all part of an overall strategy to prevent the government forces from enforcing the prohibition rice export.